Reading Kenya: Maandamano Books

Some are better than others. The writing of them is still essential.

I attended Too Early for Badassery last weekend, an edition of the Too Early for Birds (TEFB) theatre production centred on the stories of memorable Kenyan criminals from our history. I got myself two t-shirts, one featuring the iconic Tom Mboya hat — an ode to TEFB’s excellent Tom Mboya show — and one that says “I’ve attended every show”. Because I have. I also got a bunch of books, three of which speak to our present political moment.

During last year’s demonstrations, calls rose for storytellers to do what storytellers are supposed to do. At the Nuria Bookshop stand before the show, I marvelled at how seriously Kenyan writers seem to have taken this call. I figured that as the country prepares for more protests, I would find out what the storytellers have been cooking over the past year.

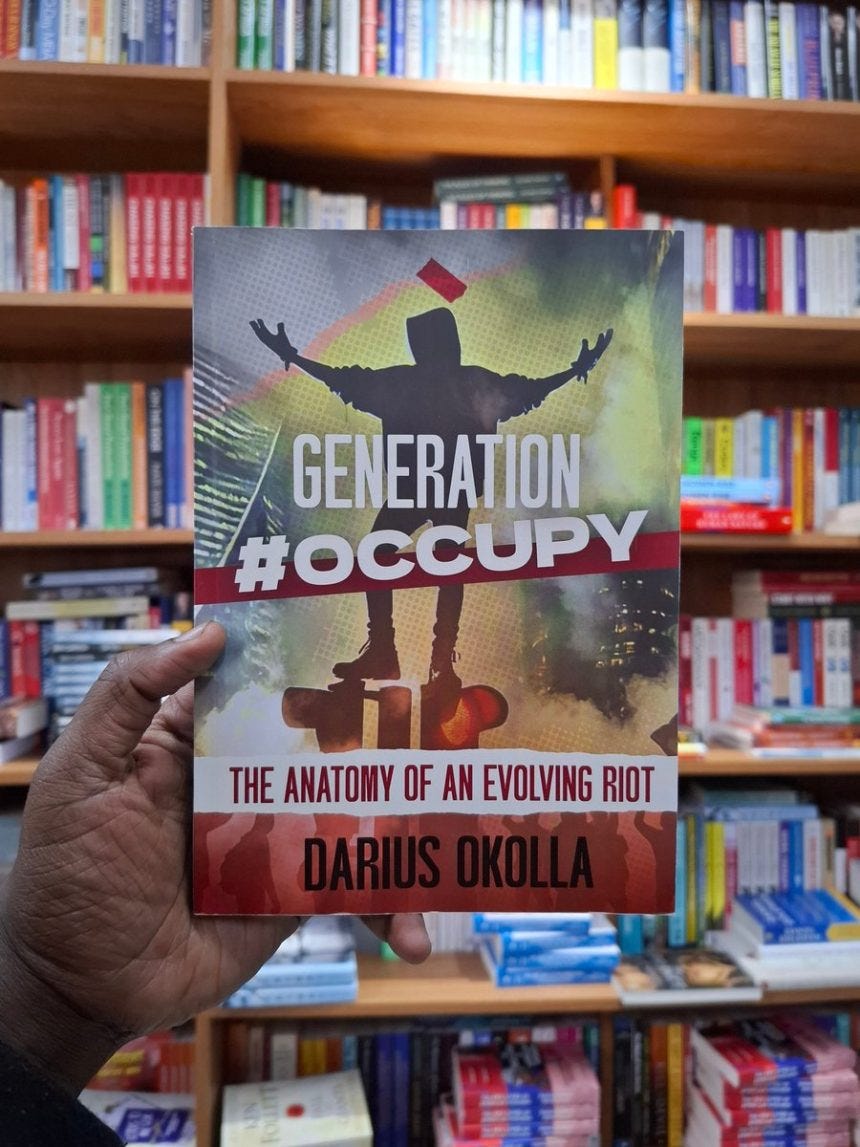

I am yet to get through the maandamano books I got, but I can already say, when they are good, they are really good. When they are bad, it feels like this is why we can’t have nice things as a country. The two shown here are great. Generation #Occupy comprehensively describes last year’s protests while situating them within greater cultural context. Read more about it on Ukombozi Review. Patriotism and Visionary Leadership, while I am salty about the generic title (It was originally, the author says in the book, Autocracy to Anarchy: The Metamorphosis of Democracy in Kenya. Look how much more interesting that is!), is doing a great job tracing for me how we ended up here as a people, from the inequalities entrenched by colonisation to the lunatic politics of the present-day, and how we might move forward. The third one disappointed me in every way a book could possibly disappoint me, and it is the reason I am writing this — so that my irritation can take a hopefully useful form for others figuring out how to write and publish their books. Below, a series of points summarising my thoughts.

If you have to pad a book with pages upon pages of accolades and nice things people with nice titles had to say about it, then perhaps a consideration is in order of why credibility needed to be built this way. That said, the manufactured credibility did work — I bought the book, didn’t I? The downside is that I ended up feeling duped when the credibility in question turned out to be masking the absence of substance.

“Foreword by So and So” does not belong on the book spine. Especially not before both the book title and the author’s name. Especially, especially not when it is written “Forwarded by So and So”. Especially, especially, especially not when the foreword in question turns out to say nothing specific about the book’s contents and is only a page long. It gives riding on an acquaintance’s name recognition, and it is poor form.

People write blurbs to support the author and help garner attention for the book. You want your blurb to sound smart, to praise the book and its author, to persuade people that this is worth the 1500 bob they will spend. So you use words like “transformative”, “beacon of leadership”, “bold”, “unwavering”, “thought-provoking”. For good measure, maybe you pass your praise through ChatGPT to make sure it sounds as impressive as possible. All well and good. I imagine this is the sort of task ChatGPT was made to help with. What I will say, though, is that when 10 different blurbs in one book sound the same in language and tone, and when one blurb describes the book as “outstandingly specific and sincere” in one sentence and then as “outstandingly earnest and precise” in the very next sentence…the reading experience and a reader’s expectations are disrupted significantly. Maybe as an author you only need three genuine ones, you know?

Your book probably does not need a Foreword, a Preface, and a Chapter 1 all talking about what inspired you to write the book, how transformative it is, and what you hope it will achieve. The foreword is written by someone other than the author, and it’s purpose is to offer an endorsement of the book. The preface is written by the author and offers some context about the writing of the book and its subject matter. A good editor will ensure your book does not have a generic foreword, a preface written by an unknown third-party speaking of the author in third-person (which should have been in the foreword), and then a first chapter dedicated to outlining the author’s journey to the book (which should have been in the preface).

A good editor will also ensure you do not have the same quote appearing in different chapter epigraphs and dedicated to different people. And they will also ensure you know that you need to seek permissions to use copyrighted text in your epigraphs.

The biggest reason to work with a competent editor from your first complete and coherent draft is that they can tell you whether or not your manuscript is structurally sound and contains enough substance to actually power a book. Sometimes what you think is a book is actually a blog post. Or a series of tweets. Or an opinion piece in a daily newspaper. Sometimes the idea is wonderful but the execution needs work. Sometimes the framing is off or you’re assuming the wrong target audience. What goes into developmental editing will then also feed marketing because you will be clearer on who your message is for and what the message is and why the message matters at all. With a topic as potentially inflammatory as maandamano — a literal fight for our democracy — it matters that you get your facts and your framing right. It matters that you take the time to reflect, to research, to hearken back to history even while opening up to possibility. When it is clear an author knew what they were doing from the get-go, and that the book was given the time and care it needed, the resonance is unmistakeable. It’s a very different reading experience from when an author prioritised just getting the book out. Readers can tell when you rushed through not just your writing but your thinking as well.

Perhaps most importantly, it matters that your book offers more than what everyone who has been paying attention has known since last year’s demonstrations, since the elections of 2022, 2017, 2013, and 2007. You have to offer more depth and clarity of thought than we can find on Twitter and TikTok. If the purpose of your book is to document maandamano during this regime, then put on your journalistic sensibilities and tell us the who, what, why, when, and how. If the purpose is to link the past and the present to help us envision a different future, then put on your research sensibilities and retrace the path that led us here. There are many ways to draw meaning from where we now stand, many ways to imagine better. What is inexcusable is putting together a book that only regurgitates bar for bar what KOT is already agreed-upon — especially not when there is so much about our politics and governance that is differently understood and remains divisive. There is a reason it takes a while and a lot to write a good book. You have to be able to justify choosing the form.

Can people reading your book beyond your locality and beyond your present still understand what you’re saying or have you locked them out by failing to ground your narrative and argument with sufficient detail in place and time?

ChatGPT is fluent. Its sentences are smooth and clean, stripped of any tics that may be particular to a writer. I find that this is fine in, say, corporate communications. And I cannot deny that ChatGPT and others like it are useful for people who have previously found difficulty in communicating in written form in a second or third or fourth language. Looked at one way, they do democratise book writing, especially in a country where most publishing is in English and half the population does understand English but you can see where it falters. Still, the reflections and insights in a book have to be yours; that’s what allows it to matter at all. It is possible to be aided by AI while preserving a writing style that doesn’t needlessly set off people’s newly developed and still developing AI alarm bells. A good editor (a good beta reader, really) can help with this.

The ability to typeset a book does not mean the ability to design a good book cover. In a significant way, those are different skillsets, and for typical books, one requires a creativity that does not come naturally to everyone and that is difficult to teach.

That said, I genuinely think typesetting that is pleasing to the eye is the bare minimum you owe me as a reader — along with proper punctuation, for clarity’s sake. Some of us have reluctant eyesight; I know it is easier on the pocket to produce the book when your margins are thinner and your font is smaller and there is no spacing between the paragraphs and the paper is the cheapest bright white that you can find…but anko pls. It makes a difference, I promise.

We need and want more stories that dig deeper into why we are the way we are as a country. We need the academics to speak to us more than they speak to each other — and to assume that we are capable of holding complexity and nuance. And we need the book designers and editors to be in the room where this happens so that we can actually buy these books and enjoy them. When it all comes together like this, it truly feels like change is at our door.

Great points and nice to know people actually care about the details. 💯

hope you hadn't bought the AI generated book before you noticed all that